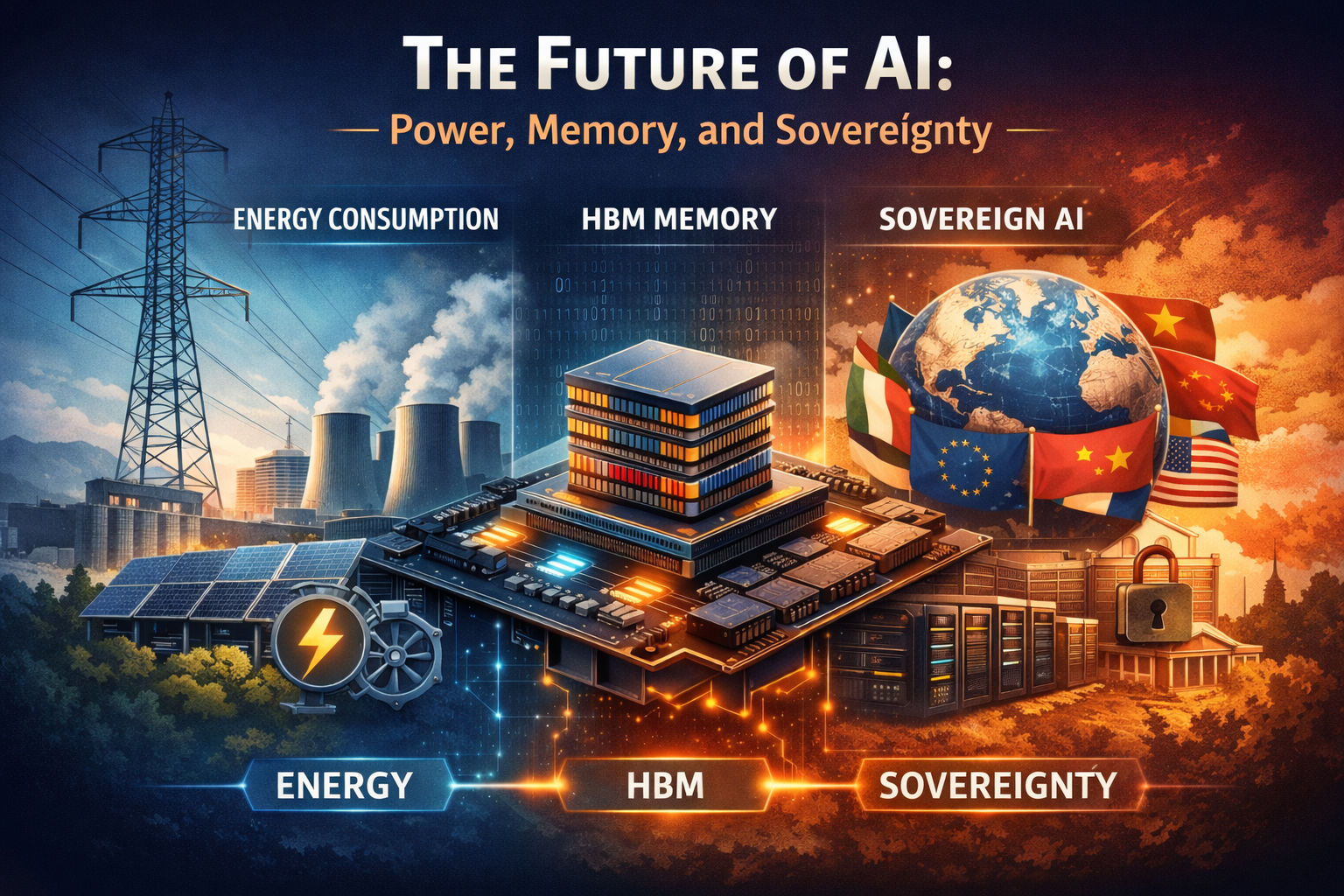

Artificial intelligence is no longer an abstract research challenge solved in code alone—it is now constrained by energy systems, memory supply chains, and geopolitical ambitions for AI autonomy. As models become more capable and more widely deployed, these physical and strategic forces are shaping the trajectory of the entire field.

Spoiler: it isn’t only the next transformer tweak. Below, we map the three material forces—energy, memory, and sovereignty—that will decide which organisations, and which nations, can still scale intelligence in the years immediately in front of us.

AI’s new energy footprint

AI data centres are becoming one of the fastest-growing segments of global electricity use. According to a recent International Energy Agency (IEA) report, global data-centre electricity consumption is projected to more than double to around 945 TWh per year by 2030, largely driven by AI workloads. This figure is significant: it would be roughly equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of a medium-sized developed country and represents continued rapid growth versus earlier years.

Energy demand from AI isn’t just about training large models once. The proliferation of inference workloads—where models respond to millions of real-time queries—means datacentres increasingly draw baseline power continuously, rather than sporadically. This trend is already affecting grids, as seen in local utility reports and energy policy discussions.

Memory constraints: HBM under pressure

Modern AI hardware performance hinges not merely on raw compute (FLOPS), but on High-Bandwidth Memory (HBM) capacity and bandwidth. HBM enables accelerators (such as those used for training and inference of large language models) to move data quickly enough to keep computational units busy.

Recent global supply chain reporting confirms a tight memory market with constraints driven in part by AI demand. Reuters and industry analyses have documented shortages of advanced memory chips, with producers diverting capacity toward high-end memory types and prices rising across DRAM and HBM categories – Reuters.

More granular memory market analysis shows that this trend has tangible effects: manufacturers such as Micron are prioritizing advanced memory for AI infrastructure and reducing consumer offerings, reflecting the strategic importance of memory for large-scale AI.

Sovereign AI: strategic autonomy

The rise of AI has triggered policy responses from governments seeking sovereign control over critical AI infrastructure. This “sovereign AI” movement encompasses:

- national or regional compute clusters,

- domestically controlled training datasets,

- pipelines for secure model development,

- and regulatory frameworks to ensure accountability and resilience.

This is most visible in multi-national initiatives in Europe and other regions, where AI infrastructure and data governance are framed as strategic priorities. Several EU policy analyses and proposals explicitly tie local compute capacity and data governance to broader economic and security goals.

The three-cornered constraint

Rather than a single bottleneck, the future of AI will be shaped by a trade-off triangle:

- Energy availability and cost, as AI workloads draw increasing grid power.

- Memory supply constraints, with HBM and associated technologies in limited supply.

- Infrastructure sovereignty, with nations competing to secure local model and compute ecosystems.

When one side tightens, the ecosystem adapts—through model optimization (e.g., quantization, distillation), strategic allocation of compute and memory, and jurisdictional realignment of infrastructure assets.

Conclusions

AI progress is no longer a purely algorithmic contest. It is now a systems-level challenge requiring coordination across energy policy, semiconductor manufacturing, national technology strategy, and cloud-to-edge infrastructure planning. In this landscape, infrastructure strategy becomes AI strategy.

The next wave of AI leadership will not be decided in research labs or benchmark leaderboards, but in power stations, memory fabs, and ministries of industry. The organisations and nations that treat electricity availability, HBM supply, and sovereign compute as first-class AI design variables will define the pace of innovation for the next decade. In the era of foundation models, owning the stack is no longer an efficiency play—it is a strategic necessity.

Yet the identity of the future AI superpowers remains profoundly uncertain. Leadership will not simply accrue to today’s technology giants or geopolitical incumbents, but to those able to synchronise fragile industrial ecosystems under volatile political, economic, and environmental conditions.

This raises an unavoidable question about the global character of AI progress: will the leaders of the next AI era treat breakthrough capabilities as shared scientific infrastructure, or as strategic assets to be ring-fenced behind national and corporate borders? As energy scarcity, memory shortages, and sovereign compute initiatives intensify, incentives shift from openness to control. The likely outcome is a more fragmented AI landscape, where access to frontier models is shaped less by innovation and more by geopolitics, trade policy, and industrial leverage.

“The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom”

Isaac Asimov